These days I'm feeling not so much a film journalist and more a circus act, juggling film festivals while balancing a tight rope on rollerskates. Twitch sent me and contributing Evening Class writer Michael Hawley down to cover the Palm Springs International Film Festival; Larsen Associates had me cover San Francisco's Berlin & Beyond; I launched into San Francisco's Noir City Friday evening, and S.F.'s IndieFest is looming menacingly around the corner. If I go off balance, lose my skate key, and drop a ball now and then, please forgive.

PSIFF's Cine Latino program was especially inviting this year. I wish I could have taken much more advantage of their fare, but, am grateful for what I got to see.

From Mexico, I was eagerly anticipating Juan Carlos Rulfo's In the Pit (En el Hoyo, 2005), which came highly recommended to me by Sergio de la Mora, who graciously sat through it one more time with me. In his Bay Guardian capsule Sergio succinctly wrote, "Director Juan Carlos Rulfo finally lets his famous father rest in peace while dynamically exploring his own voice. This documentary brings together on-site conversations with workers who constructed the second level of the highway where three million cars circulate daily through Mexico City."

In The Pit won Best Film at the 2006 Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema, Best Documentary at the 2006 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, the Grand Jury Prize for World Cinema-Documentary at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival, the Jose Cuervo and Audience Award for best documentary at the Morelia Film Festival, and was awarded the Knight Grand Jury Prize of $25,000 in the World & Ibero-American Documentary Feature Competition at the Miami International Film Festival.

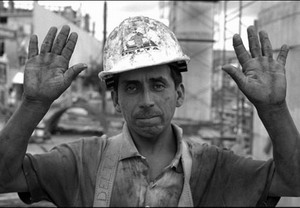

As the film's website attests: "The pit is but the pretext . . . what you encounter is life." Or as Variety's Robert Koehler puts it, this documentary about the building of the flyover or second level of Mexico City's Periférico freeway—Mexico's most controversial project in the last decade necessitated by the more than 3 million cars in Mexico City today—is "[m]ore an inquiry into what makes working people tick than a study of the project itself, the pic highlights the human dimensions involved in any huge public project." Fipresci's Lucy Virgen notes the similarity of its faithful, poignant portrait of Mexico's working class with Jia Zhang-ke's Dong. Nick Schager at Slant distinguishes that the film isn't "an overt critique of socio-economic divides as it is simply a compassionate attempt to shine a light on its subjects' individuality and basic humanity."

Rulfo accomplishes this by focusing on a handful of albañiles (construction workers); a cast of characters who infer Everyman. If their language is not glutted with profane sexualizations—"El Grande" harasses "Shorty" by feminizing and fetishizing his butt—then it elevates into suspicious incant as Natividad recirculates the ancient Mexican legend that—for every bridge being built—the devil asks for one soul, in exchange for the bridge never to fall. Natividad is convinced the devil has claimed more than his due.

"[G]rounded in the conviction that audiences with their eyes wide open will draw their own conclusions", Rulfo observes how this team works "in subterranean pits built to shore up the pillars that support the second deck, as well as high above to insert thousands of steel rods to reinforce the concrete columns and blocks that comprise the deck." A quick glimpse at the photo section of Rulfo's IMdb profile extols the vertiginous camerawork he undertook for nearly four years. Along with Rainer Hoffmann's riding the rails to El Norte, Rulfo reminds that a true documentarian is not opposed to dirt or the salt of sweat or stepping into the lives (and work shoes) of his subjects. "Juan Carlos Rulfo may talk like a construction worker," Lucy Virgen comments, "but he shoots like a great filmmaker." As much as Rulfo asserts that he has tried to remain invisible, however, and as much as Virgen credits him with this, it takes perhaps a Mexicana like Native Stranger's Nayeli to catch the subtle way the film's subjects nickname Rulfo güero (blond) and defer to him as "usted" instead of "the informal tú"—"indication of the difference in social status between them."

The documentary's sound design is incredible. Schrager writes: "In the Pit is a documentary defined by symbiosis, its melding of musical instruments with construction site sounds (clanging jackhammers, crunching iron, screeching machinery) a sonic reflection of its portrait of men becoming intimately, inextricably associated with their artificial creation."

Across the board with critics, it is the documentary's coda—a sweeping, 6-7 minute helicopter scan of the Periférico freeway under construction—that stunningly contextualizes the immensity of the project and the number of individuals necessary to construct this architectural mammoth. You're lifted out of the world of one work team to witness the labor of hundreds and its impact upon millions. The effect is transcendent.

Cross-published at Twitch.